Welcome to Carbon Risk — helping investors navigate 'The Currency of Decarbonisation'! 🏭

If you haven’t already subscribed please click on the link below, or try a 7-day free trial giving you full access. By subscribing you’ll join more than 3,000 people who already read Carbon Risk. Check out what other subscribers are saying.

You can also follow my posts on LinkedIn. The Carbon Risk referral program means you get rewarded for sharing the articles. Once you’ve read this article be sure to check out the table of contents.

Thanks for reading Carbon Risk and sharing my work! 🔥

Being able to accurately gauge the potential size of a rapidly growing market is vital if investors aren’t to waste precious capital developing businesses, especially if better risk-adjusted opportunities are available elsewhere. The voluntary carbon market (VCM) is one such business where investors periodically question just how big the market could become.

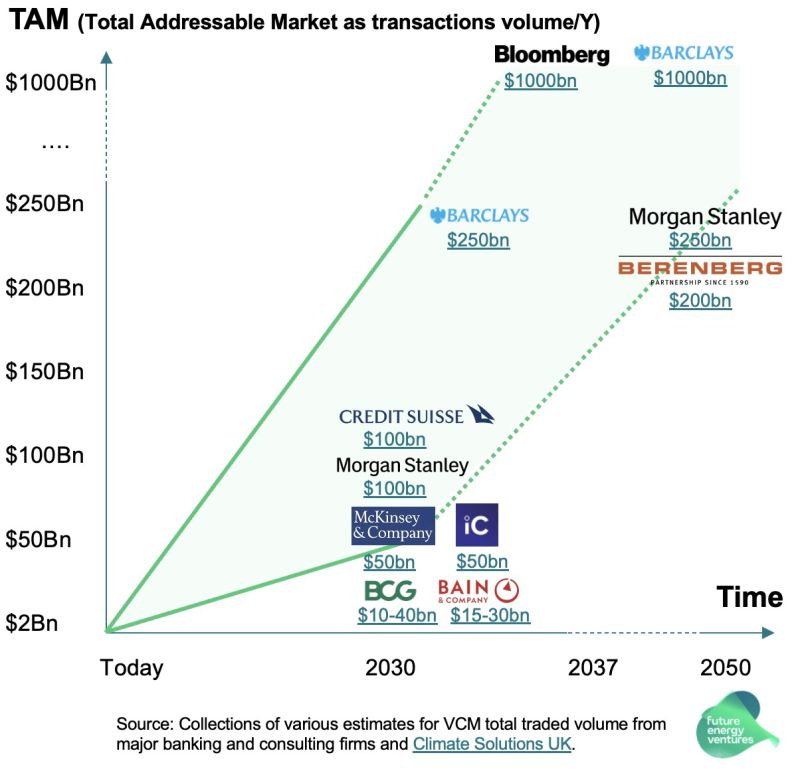

Giancarlo Savini from Future Energy Ventures recently shared the chart below on LinkedIn. Based on projections compiled from a range of investment banks and consultancies, it suggests that the VCM could grow from $0.50-2 billion today, to $10-100 billion by 2030, before surging towards $200-1,000 billion by 2050.1

I only have limited access to how the projections outlined in the chart were prepared, with many only being covered very lightly in news reports (see footnotes). If any of my subscribers have more details (or even links to the underlying analysis) then please share in the comments, or by contacting me directly. It’s probably not an exhaustive list of projections, but it’s a good enough place to start.

I’m also not convinced that the numbers presented in the chart necessarily reflect the latest thinking by each institution, or indeed are necessarily comparing apples with apples. For example, Berenberg put out a figure of $200 billion for 2050 over 3 years ago, and the bank doesn’t appear to have updated it’s thinking since then, at least not publicly.2

With those caveats in mind, I thought it might be worth adding some context behind the high level numbers, to try and unpick what is important, uncover where the biggest source of uncertainty lies.

Lets start off by saying that the carbon credit market VCM in 2030 (and certainly by 2050) is likely to look very different to where we are today. The first thing to get right is the terminology. The VCM is commonly used as an abbreviation for the voluntary carbon market. However, it’s worth tweaking the terminology slightly to give a better sense of what the market is likely to become. Rather than voluntary, lets start calling it the verified carbon market.

The VCM will still include companies voluntarily channelling capital into funding carbon projects, but it will increasingly be an integral part of regional and global carbon compliance regulations. Ensuring that carbon avoidance and removal claims can be verified will be vital to their integrity - whether that demand is voluntary or compliance.

It’s not always clear from the various projections what assumptions have been made regarding the split between compliance and voluntary demand for carbon credits. BCG explicitly assumes that ~80-90% of demand for carbon removal’s will be voluntary purchases by 2030-40. What assumptions been made by other analysts is much less clear.

How will the balance shift between avoidance and removal credits? Avoidance credits have dominated the VCM, accounting for around 80% of the volume of credits issued over the past 5-10 years. However, over the rest of the decade avoidance credits are projected to fall to around two-thirds of the market, according to Shell/BCG with removal credits accounting for one-third of credits issued. As the market focuses on the need for carbon removal this proportion is likely to dominate the market, but the speed at which it does so is highly uncertain. The balance between avoidance and removal credits feeds into the next question.

How much will carbon credits cost in 2030 and 2050? Assuming demand for carbon credits moves towards a removal centred market then we need to make an assumption on how demand and supply for nature and technology based carbon removals evolve over the next two and a half decades. Forests, soil, mangroves, biochar, bio-energy with carbon capture and storage (BECCS), direct air capture (DAC) and enhanced rock weathering (ERW) will each face their own resource constraints, limiting their expansion. In the short-medium term it’s likely that demand will grow much faster than supply can realistically respond.

What about the cost evolution of technology-based carbon removals? Direct air capture (DAC) is currently the most expensive form of carbon removal, but arguably has the greatest potential to scale. If the cost can be brought down from the ~$400 per tonne mark to nearer $100 per tonne then this will force other carbon removal methods to compete. But for that to occur capacity needs to expand rapidly, generating learning effects that bring costs down even further. By its very nature that process and the timing is highly uncertain. Finally, a substitution effect could result in increased demand for nature-based removal, and a subsequent rise in the price of those credits towards technology based credit prices (see Technology-based carbon removal credits crucial if net-zero targets are to be met).

How much carbon actually needs to be removed? As I’ve discussed in previous articles, we are going to need carbon removal to stand any chance of getting to net zero by 2050. We can’t simply wait until the 11th hour to start investing in carbon removal. It needs to start happening today. However, as Robert from

outlines, there is more than one reason why we should want to invest in carbon removal and it makes a big difference to how much carbon needs to be removed.3Robert estimates that the world will need 2-5 Gt per year of permanent carbon removal to offset continuous residual carbon emissions and halt the global increase in temperatures. However, that isn’t the end of the story. Methane and nitrous oxide gases are significantly more powerful than carbon dioxide in warming the planet, account for a significant share of emissions (especially from agriculture), and are very difficult to eliminate. The impact of the former is relatively short-lived (20 years), while the latter stays in the atmosphere for 100+ years.

Offsetting the global warming impact from rising methane emissions would require a multiple Gt’s per year of carbon removal (Robert puts it at 13 Gt per year), plus 1-2 Gt per year of carbon removal to account for nitrous oxide. Overall, potentially up to 20 Gt per year of carbon may need to be removed by 2050. That’s a factor of 3-4 times higher than what many of the banks and consultancies have pencilled into their projections.

If we assume that carbon credits trade for $100 per tonne in 2050, and that 5 Gt per year is removed or otherwise avoided, then that puts the market size at $0.5 trillion. If we also take account of the other GHG’s (methane and nitrous oxide) then the market could be worth $2 trillion (again assuming $100 per tonne). However, both of these estimates include both voluntary and compliance demand for credits. How much of this demand will be voluntary?

What about all of the other ancillary services that make the VCM possible? There is going to be increased demand for services that can monitor emissions in real time and be able to accurately report and benchmark different GHG emissions. The global oil and gas methane detection market alone could be worth almost $1 billion by 2025, according to projections from BNEF. That’s just one industry, and one greenhouse gas. Any projection of future market value also needs to consider the role of standard setting, verification bodies, carbon credit rating agencies, project developers, carbon credit exchanges, technology providers, and the ongoing cost of carbon storage, etc. (see The carbon tracking opportunity: Real time tracking of GHG emissions and carbon sinks is a huge growth market).

Overall, the speed at which the VCM market is evolving means its almost impossible to compare one projection to another. Unless we are clear what definitions and assumptions underpin the analysis it’s impossible to be clear. Nevertheless, the projections outlined in the chart provide a reasonable guide to what the verified carbon market could be worth in 2050. One trillion dollars is achievable, although it will require many economic, political and technological stars to align.

A 'green' unicorn

“It is my belief that the next 1,000 unicorns — companies that have a market valuation over a billion dollars — won’t be a search engine, won’t be a media company, they’ll be businesses developing green hydrogen, green agriculture, green steel and green cement,” - Larry Fink, CEO and Chairman of Blackrock, 25th October 2021

https://www.linkedin.com/feed/update/urn:li:activity:7104660442609799168/

https://www.spglobal.com/commodityinsights/en/market-insights/latest-news/natural-gas/051320-global-carbon-offsets-market-could-be-worth-200-bil-by-2050-berenberg#:~:text=%22The%20global%20carbon%20offset%20market,Berenberg%20said%20in%20the%20note.

https://www.morganstanley.com/ideas/carbon-offset-market-growth#:~:text=With%203%2C800%20more%20projects%20listed,around%20%24250%20billion%20by%202050.

https://www.shell.com/shellenergy/othersolutions/carbonmarketreports.html#vanity-aHR0cHM6Ly93d3cuc2hlbGwuY29tL2NhcmJvbm1hcmtldHJlcG9ydHMuaHRtbA

https://www.sustainabletimes.co.uk/post/report-global-voluntary-carbon-credit-industry-estimated-to-hit-250bn-by-2030

https://www.bloomberg.com/professional/blog/long-term-carbon-offsets-outlook-2023/

https://about.bnef.com/blog/carbon-offset-market-could-reach-1-trillion-with-right-rules/#:~:text=Demand%20for%20high%2Dquality%20offsets,to%20%2432%2Fton%20in%202050.

https://www.bcg.com/publications/2023/the-need-and-market-demand-for-carbon-dioxide-removal